2017: What We Did

Thank you so much for your support of the Kimmela Center this year. Our mission is to apply the best science to the work of animal protection, and here are some of the highlights you made possible this year through your tax-deductible donations.

The Someone Project

This joint Kimmela Center / Farm Sanctuary venture brings together current scientific evidence for cognitive, emotional and social complexity in farmed animals and publishes the results to the scientific community and to the general public.

Our latest papers explore the cognitive, emotional and social capacities of chickens and cows. We conclude that chickens have a sense of self in relation to other chickens, that they learn through observing others, and that they engage in perspective-taking and deception when competing for mates.

Our latest papers explore the cognitive, emotional and social capacities of chickens and cows. We conclude that chickens have a sense of self in relation to other chickens, that they learn through observing others, and that they engage in perspective-taking and deception when competing for mates.

And we note that cows have positive emotional reactions to learning, need friendships to buffer them from depression and anxiety, and are fiercely protective as mothers.

Thinking Chickens: A review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken.

Download the peer-reviewed paper.

Download the white paper.

The Psychology of Cows: A review of cognition, emotion, and the social lives of domestic cows.

Download the peer-reviewed paper.

Download the white paper.

I discussed these papers in a talk I gave to kick off the annual Farm Sanctuary hoedown in Watkins Glen, New York.

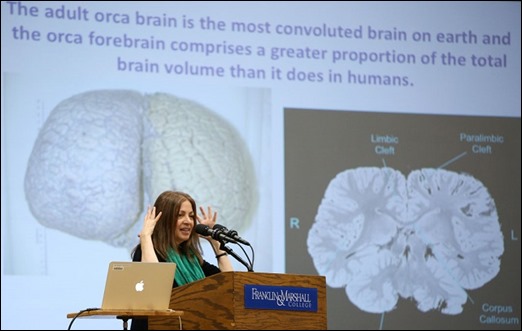

Outreach for Dolphins and Whales

At conferences and colleges from Barcelona to British Columbia, we have been bringing the message of the plight of captive dolphins and whales to the scientific community, the zoo and aquarium community, the legal world, the student world, and the general public. I am heartened by the fact that students and young professionals at home and abroad want to become scholar-advocates for our fellow animals.

You can watch a video of one of these talks, to a group of students at Franklin & Marshall College, here.

Plans for Superpod 6

The scholar-advocacy program for students and young professionals at Superpod 5 in 2016 was such a success that we are doing an expanded version this year. Early details of the conference on San Juan Island, July 16-20, are here.

Legislative Efforts: Applying the Science

Ending display of captive cetaceans in Canada: In March, our team testified on three occasions to the Canadian Senate Committee on Fisheries & Oceans in Ottawa on behalf of Bill S-203, which would end keeping of captive cetaceans on display in Canada. My own testimony, available here, focused on the false claims that research with captive dolphins and whales is necessary for conservation work, and discussed our findings showing no compelling evidence that animal displays in zoos and aquariums have educational value. The bill passed through the Committee and is set to be heard by the Senate in January.

And, separately, in Vancouver: The Vancouver Aquarium is trying to overturn a Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation bylaw amendment that bans any future display of cetaceans at the Aquarium. The case was heard by the B.C. Supreme Court, and we have provided an affidavit on the scientific validity of the Park Board’s decision. We expect a decision in February.

“I Am Not an Animal!”

The Kimmela Center organized a ground-breaking two-day symposium to explore the idea that at the core of our fraught relationship with our fellow animals is the deeply-rooted psychological need to tell ourselves that “I am not an animal!”

Held in Atlanta, the event featured leaders in the fields of psychology, ecology, ethics, philosophy, law and advocacy, including Carl Safina, Hal Herzog, Sheldon Solomon and Steven Wise.

Your tax-deductible donation, large or small, will greatly help us to succeed in our mission to use the power of science to bring an end to the abuse and exploitation of nonhuman animals.

Thank you again, and have a safe and healthy New Year.

Lori Marino

Executive Director

The Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy.